Political intervention in markets is back

If the 1980s to the 2000s saw the political pendulum swing firmly towards market liberalisation, an opposite shift has been evident since the Great Financial Crisis a decade ago. Impetus for stricter regulatory control and market intervention has multiplied further during the market turmoil of 2020-2022. The Covid-19 pandemic raised government debt to eye-watering levels and highlighted the importance of diversified sources of supply for strategic products and commodities. Subsequent supply chain bottlenecks and energy shortages due to the Russia-Ukraine conflict have placed added pressure on government budgets as they seek to mitigate inflationary pressures. We have seen outright embargos by G7 nations on Russian commodity imports, financial sanctions, a Russian pipeline gas blockade on Europe, strategic petroleum stock draws aimed at capping pump fuel prices in the US and unprecedented government interventions in energy markets, notably in the G7 and EU.

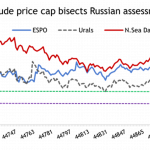

Such interventions can of course open-up new, albeit potentially higher-cost, arbitrage flows, requiring new commodity price indices. ATDM has been one such example, designed to reflect sour crude values in Europe now that Russian Urals crude is largely diverted eastwards to Asia.

Table of Contents

ToggleUnintended consequences can however also arise when governments attempt to replace long-established market indices with capped wholesale prices, potentially worsening supply tightness or unravelling long-term supply contracts based on prevailing market benchmarks.

Moreover, when geopolitical uncertainty is high, there is a political temptation to blame speculative investors for elevated commodity price volatility (and here the terms “volatility” and “higher prices” can sometimes become blurred). At such times, policy interventions themselves can inadvertently reduce liquidity in derivative markets and boost volatility. This can raise hedging costs for physical market participants, ultimately impeding the efficient flow of commodities from areas of surplus to areas of deficit.

Regardless of the political rationale for government intervention in commodity markets, such episodes have in the past tended to be long and drawn-out in nature. Given the likely extent of market and trade flow re-orientation post-Covid, and assuming ongoing conflict in Ukraine, we may not yet be at the high-water mark for regulatory response and market intervention for commodities. After all, the regulatory architecture for commodities remained a work in progress for at least five years following the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. This suggests there may be more to come for 2023 and beyond.

2. Commodity trade between Russia and China will increase

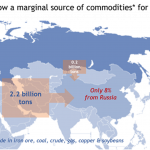

Chinese commodity imports account for up to 30% of global trade. If China is the world’s leading “absorber” of commodities, then its counterpart on the supply side of the equation is Russia. For nickel, wheat, natural gas, aluminium, coal and fertilisers, Russian exports (together with Ukraine in the case of wheat) account for some 20%-35% of total global trade in those commodities.

Yet for historical, political, logistical and geographical reasons, bilateral commodity trade between Russia and China remains comparatively limited. Taking a basket of key globally traded commodities (iron ore, coal, crude oil, natural gas, copper and soybeans), China imports a total of around 2.2 billion tons, but only 8%, or around 0.2 billion tons, is sourced from Russia. True, China sourced 16% of its near-one billion tons of oil, coal and gas imports in 2021 from Russia, but energy is an exception to otherwise under-developed trade ties between the two nations. This is almost certain to change in the months and years ahead, assuming that Russia’s historical baseload consumers to the west, in the G7 and EU nations, continue to minimise purchases and prioritise diversity of supply. For its part, China will want to ensure any such increase in offtake from Russia takes place at advantageous prices, while not endangering its supply diversification initiatives with central Asia and the Middle East.

China’s energy pivot implies new Asian growth hubs for oil

Notwithstanding China’s appetite for incremental, potentially discounted supplies of Russian oil and gas, 2022 has highlighted ongoing fundamental shifts in China’s domestic energy policy. Given its battles this year with Covid outbreaks and a slumping property sector, overall commodity imports in the first 11 months of 2022 have unsurprisingly declined by nearly -5% versus 2021 levels. In percentage terms, coal, natural gas and agricultural imports lag by the most, while mainstay imports of iron ore in November alone were -6% (or nearly 6mt) below November 2021. Real estate sector slow-down is clearly weighing on steel and iron ore demand. Copper imports (unwrought + ore combined) in contrast look much stronger, at +9% year-on-year, as New Energy Vehicle (NEV) production, plus renewable generation capacity additions continue apace. Renewable capacity additions were up by 15% in 2022, while January-November NEV sales were a stellar +100% vs. 2021. Indeed, China since 2020 has added more renewable generating capacity than the rest of the world combined. China’s Energy Transition is fundamentally a story of electrification, which will prioritise future imports of copper, alongside other key metals and minerals associated with renewables capacity, transmission/distribution network upgrades and batteries.

None of this is to suggest that China’s appetite for one billion tons per year of hydrocarbon imports will imminently diminish. But the baton for growth in terms of oil demand, after two decades of regional dominance, may now be passing away from China and towards India and South-East Asia.

Did 2022 denote a shift in energy & transition policy priorities?

The COP-27 meeting in Egypt this autumn established the principle of “loss and damage” reparations for current and past climate change impacts, although details of Advanced Economies’ payments to lower income countries remain to be decided. Much less was achieved in terms of tightening climate change mitigation measures via more ambitious national commitments and policy measures. Indeed, the UN Environment Programme projects that even with current Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), the World is headed for +2.5°C temperature rise by century-end rather than an optimal +1.5°C.

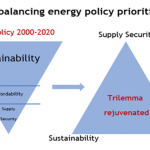

In parallel, policy makers’ experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine conflict have re-oriented short term energy policy priorities. The focus (notably in Europe) in the last 20 years has been on sustainability at the expense of security of supply and affordability. Recent crises have rejuvenated the idea of an energy policy trilemma: how to achieve sustainable, secure and affordable energy systems in the years ahead. For some, the answer is to accelerate the shift away from hydrocarbons, while for others the experience of 2020-2022 has highlighted the inadequacy of investment in hydrocarbon spare capacity and system redundancy over the last decade.

Amid-spiralling inflation, rising interest rates and elevated government deficits, there is a clear risk that Energy Transition targets for de-carbonising the fuel mix will be delayed. Indeed, some observers consider that security of supply concerns may re-open the debate on the optimal future fuel mix itself. In any future scenario of “resilient hydrocarbon” demand, greater attention will need to be paid to adaptation and abatement measures. If oil, coal and gas indeed have long tails in the post-peak demand phase, then technologies to abate carbon intensity and emissions will be needed.

ATDM Consulting sees current policies implying peak global oil demand by 2030, but thereafter a slow decline towards 80 mb/d in 2050. That is significantly above demand levels implied by the IEA’s Net-Zero CO2 emissions scenario. For the short-to-medium term it implies an increased window of opportunity for biofuels and renewable drop-in fuels such as HVO, SAF and bio-naphtha, to lower the carbon intensity of continued liquid fuel use. For the longer term, it suggests a more ambitious roll-out of carbon pricing is needed to kick-start investment in CCUS and other abatement technologies.

Structural vs. cyclical cost inflation

There are signs at end-2022 that some of the intense supply chain bottlenecks derived from the pandemic and the war in Ukraine are receding. The New York Federal Reserve’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index has fallen by 70% from its December 2021 high-point. Nonetheless, US and European producer and consumer price inflation remains high, with consensus CPI projections for 2023 remaining two- to three times central bank target levels. Most mainstream forecasts nonetheless have inflation falling back towards “tolerable” levels near 2% in 2024 or 2025.

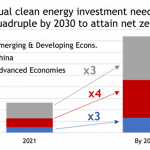

However, elements of recent energy and commodity price inflation may prove longer-lasting. LNG and European pipeline gas markets could remain stretched until 2024. Limited upstream and downstream spare capacity for oil, allied to OPEC+ revenue aspirations and ongoing uncertainty over Russian crude and products exports, suggest a floor for crude prices well above historical average levels. And Energy Transition commodities such as lithium have seen price rises well above those for hydrocarbons in 2022. Renewables generating capacity expansion and vehicle fleet electrification imply a three to four-fold increase in critical minerals and metals demand by 2030. Together with stretching supply chains and the costs of enhanced energy system redundancy, what is currently seen as a cyclical inflation episode may in reality prove more structural in nature.

Interestingly, the IEA’s 2022 estimate of annual clean energy investment requirements by 2030 to enable net-zero is remarkably close to that reported in 2021. This looks like an understatement of the true scale of the budgetary challenge if critical materials inflation indeed becomes embedded.

- Macro-economic slowdown is already here

Third quarter 2022 global GDP growth was flattered by a partial re-opening of China’s economy after the spike in infection rates and associated lockdowns seen in the second quarter. The Advanced Economies (AEs) have seen sharp slowdown so far this year, not least in manufacturing output, after the post-pandemic bounce enjoyed in 2021. Supply chain bottlenecks and energy price spikes following the Russian invasion of Ukraine have driven consumer price inflation towards double-digit levels year-on-year. Unsurprisingly, central banks have responded with monetary policy tightening after more than a decade of low inflation, cheap finance and quantitative easing. At issue is whether they can restrain inflationary pressures without creating a prolonged hit on employment and growth.

A second key uncertainty surrounds China’s abrupt re-opening of its economy from December 2022 and the risk that Covid infections and death rates spiral out of control. The authorities, following civil protests in urban areas, have reversed a “Dynamic Zero-Covid” policy heavily promoted at the Party Congress as recently as October. There are concerns that any resultant spike in infections could risk winter death tolls of one million people or more, given relatively low vaccine uptake by older segments of the population, and comparatively limited Intensive Care Unit (ICU) capacity at hospitals.

China also confronts headwinds in the construction sector. An enforced squeeze on real-estate liquidity after years of excess has seen investment, construction starts and housing sales all plummet, leaving a swath of property developers on the edge of bankruptcy. Now however, with real-estate accounting for 25-30% of China’s GDP, and a crucial source of income for local governments, Beijing has announced 16 key support measures aimed at preventing asset price collapse. Nonetheless, ongoing default risk and loss of investor confidence will likely continue to haunt the sector in 2023, suggesting at best a shallow L-shaped recovery after two years of contraction. As is likely to be the case in the Atlantic Basin however, public infrastructure spending should remain strong in 2023, helping to underpin a recovery in Chinese GDP growth to +4% from +3% in 2022.

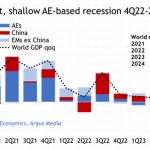

Globally, we assume that gradual economic recovery takes hold from mid-2023 onwards, after a marked slowdown for both the ex-China emerging markets and the Advanced Economies during the 4Q22 to 2Q23 period. On an annualised basis, GDP growth slips to only +1.3% in 2023, less than half the 2022 level, before recovering to +2.9% in 2024. Not surprisingly, Russia, Ukraine and Europe face the weakest 2023 profile, given an assumption of ongoing hostilities in Ukraine and resultant disruption to commodity flows. The US also skirts with recession early in 2023 while Latin America also experiences comparatively anaemic growth, continuing a slow-down that has become evident in the course of 2022.

This relatively mild recession scenario for 2023 is subject to downside risks. Renewed Chinese lockdowns or a disorderly collapse in China’s property sector would undermine such a scenario. So too an over-aggressive monetary tightening by Advanced Economy Central Banks. A worsening crisis in Ukraine and heavier-than-expected Russian energy export losses provide a third potential risk. Sustained USD strength and higher interest rates could also prompt an Advanced Economy property crisis or multiplying Emerging Market debt defaults, albeit none of these bearish risks yet form part of our base case scenario.

7.Geopolitics may trump economics for energy markets in 2023

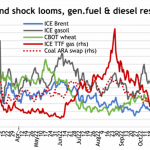

Economic slow-down implies energy prices next year will undershoot those in 2022 but a prolonged collapse seems unlikely. Demand will weaken alongside the macro downturn, but Europe will see sustained hub gas price strength to ensure continued LNG inflows to replace lost Russian pipeline supplies. December-to-date pipeline gas deliveries from Russia to Europe are running at only 10% of average 2019/2020 levels (Russia was already shorting supplies in late-2021), with the gap being mainly filled with increased LNG imports. While gas prices in both Europe and Asia have receded from August highs, the premium of European TTF to NE Asian spot LNG has widened to $7-$8/mmbtu for the balance of this winter.

Jittery winter fuel markets, and ongoing European power sector demand will likely also support thermal coal prices during 2023. However, with domestic supplies likely adequate to meet next year’s Chinese and Indian demand growth, and rising exports expected from Australia, Colombia and the US, coal prices overall should weaken from 2023 highs.The impact of successive political interventions in the bitumen market has yet to become fully apparent. With crude futures around $80 at mid-December amid recession fears, speculation is rife over renewed OPEC+ intervention to place a floor under prices, after a 2mb/d cut to output quotas effective from November. Should recession fears push crude lower towards $70, this may also trigger US government purchases to begin partial replenishment of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. The SPR was tapped to the tune of 200mb over the course of 2022, with steepest draws occurring ahead of November’s mid-term elections. Europe also introduced its embargo on Russian crude imports on 5 December, with an associated G7 price cap at $60 designed to enable continued export shipments to markets in Asia and other non-G7 destinations. Moscow continues to threaten to curb exports to any territory complying with the price cap, though currently export flows continue unimpeded as market prices for the bulk of Russian crude remain close to, if not below, the $60 cap. Nonetheless, the threat of lower Russian crude supply, and all the more so diesel when the EU’s products embargo kicks in in February, is likely to provide a prop for prices. Add in scant upstream and downstream spare capacity following a post-2014 slump in investment and it looks as though crude prices could retain some support, despite a widely anticipated economic slow-down.